READ MORE ABOUT ANTIQUES

The Mystery of the Car Boot Teapot: Fact, Fake, or Forgotten Master?

Introduction: From Car Boot to Clay Treasure

What is a car boot sale? For those unfamiliar, it’s a uniquely British tradition. Imagine this: people load up the unwanted contents of their homes into the back of their cars, drive out to an organized event—often held in a field somewhere—and sell their goods from makeshift tables set up behind their vehicles. You can find anything at these events: gold jewellery, forgotten family heirlooms, even lost masterpieces. And in my case, this week? A piece of Yixing pottery that may just turn out to be a once-in-a-lifetime find.

My name is Walter O’Neill. I’ve been involved in the world of antiques in one way or another for around 30 years. I’ve always prided myself on finding the best pieces I can afford, and though I’ve spent years trying to wrap my head around Asian art, I still humbly consider myself a beginner in that field.

One quiet Thursday morning, I was walking around a small car boot sale in South Wales, UK. I wasn’t expecting much—just browsing to see what caught my eye—when I reached into a box of bric-a-brac on the ground and pulled out the most beautiful Yixing teapot I’d ever seen. Technically brown, but made from the famous “purple clay,” it had a sculptural quality that was simply stunning. The teapot was signed on the base in Chinese script, with applied panels decorating its surface. Instinctively, I knew it was something special.

I showed it to a few fellow dealers at the sale, and we all admired its craftsmanship. That morning, I couldn’t stop researching—scrolling through articles, auction records, and pottery references on my phone, my heart racing with the hope that I’d found something truly important. It’s hard to describe the excitement. The closest I can compare it to is the feeling of a child on Christmas Eve: adrenaline, imagination, anticipation.

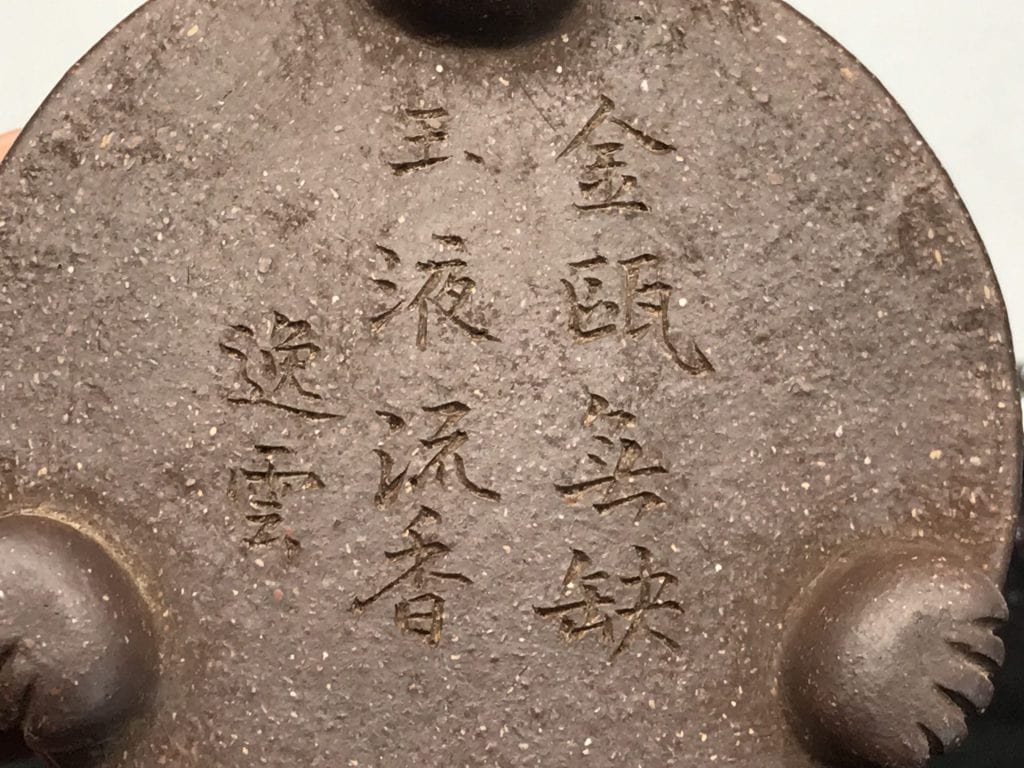

But despite hours of searching, I was getting nowhere. Eventually, I was encouraged to post it in a specialist Yixing pottery group on Facebook. Someone there identified the mark as “Yi Yun” and pointed out the presence of an eight-character poem—only to quickly dismiss the pot as a modern reproduction.

I’ll admit, I felt a bit deflated. I even listed it for sale on my website, thinking perhaps I’d been caught up in the thrill of the hunt. But something didn’t sit right with me. The quality of the pot was just too good. So, I dug deeper.

That’s when things started to change.

I soon learned that “Yi Yun” is the studio name of Lu Shuoliang — a celebrated, living master of Yixing pottery. That revelation sent me down a rabbit hole of discovery that changed everything I thought I knew about this piece. Before we go any further, let me share what I’ve learned about the man behind the name — and why this teapot may be far more important than I first realised.

🧠 Who Is Yi Yun?

Understanding Master Lu Shuoliang, His Legacy, and His Signature Style

Lu Shuoliang, who works under the art name Yi Yun (逸云), is a nationally celebrated master of Yixing Zisha (purple clay) pottery, born in 1949 in Yixing, Jiangsu province — the historical birthplace of Zisha pottery.

📚 Scholarly Roots & Family Influence

Lu Shuoliang grew up in a scholarly household. His father, Lu Ziyu, was a respected teacher of ancient Chinese literature and a connoisseur of Zisha art. Lu Ziyu personally knew legendary Zisha artisans such as Gu Jingzhou and Pei Shimin, and would often collaborate with or commission them to make pots in line with his own poetic and artistic visions.

This literati influence laid the foundation for Yi Yun’s work. From a young age, Lu Shuoliang studied calligraphy, poetry, painting, seal carving, stone engraving, and sculpture — disciplines that would later define the cultural richness of his teapots.

🛠 From Woodwork to World-Class Zisha

Before he became a full-time artist, Lu Shuoliang spent over 13 years working in mechanical wood molding and furniture decoration (starting in 1970). This precision-based work gave him an unusual edge in technical execution and spatial design when he transitioned to pottery.

In 1984, he officially entered the Zisha world as a designer and potter, starting his studio Yunxi Jingshe (云溪精舍). His journey was self-taught and painstakingly slow, often taking weeks or even months to finish a single pot — all without a master guiding him.

🏆 Achievements, Awards & Museum Recognition

Yi Yun has since been recognized as one of China’s Top 10 Zisha Masters. He received gold medals, national honors, and prime-time television coverage for his contributions to Chinese craft and design:

📺 Media Coverage

- Featured in CCTV-4 and Beijing TV

- Appeared on CCTV’s ‘Appraising Treasures’ — a rarity for a living Zisha artist

🏛 Museums that Collect His Work

His pieces are permanently held in multiple major institutions:

- The Palace Museum, Beijing

- National Art Museum of China

- National Museum of China

- Nanjing Museum – acquired 15 of his works in one go

- Taiwan History Museum

- Famen Temple Museum, Xi’an

🧪 Techniques & Innovation

Yi Yun is not a traditionalist — he is an innovator. He pioneered the fusion of ancient Chinese bronze aesthetics into soft Zisha clay, producing pieces with the look and grandeur of ceremonial bronze but with the warmth and delicacy of purple clay. His process involved intense experimentation:

- Custom blended clay recipes

- Bronze-like textures and forms

- Layered shield panels (often inspired by Han or Tang bronzeware)

- Poetic inscriptions and calligraphy

- Relief carving of landscapes, dragons, figures, and Buddhist motifs

- Multiple clay tones and highly detailed symbolic sculptural elements

Yi Yun’s forms are not just vessels — they’re visual narratives. His “Zhuni Panlu Pot”, decorated with Nine Dragons, was so impressive it was acquired by the Palace Museum after winning a national gold medal.

✒️ Key Marks & Signatures

Yi Yun typically signs his work with his art name 逸云, usually inscribed by hand in brush-style calligraphy, not sealed. Many works also carry multi-line Chinese poems, often inscribed on panels. These are rarely mass-produced or stamped — instead, they reflect high craftsmanship and cultural storytelling.

✅ Checklist: How to Spot a Teapot by Yi Yun

Here are some known traits and techniques associated with Yi Yun’s work. A genuine piece may feature some or most of these:

| Technique or Feature | Found on My Teapot? ✅ |

| Textured finish to simulate bronze | ✅ |

| Relief-carved poem or text (not stamped) | ✅ |

| Applied panels or shields | ✅ |

| Signature “Yi Yun” (逸云) in calligraphy | ✅ |

| Mixed Zisha clays and experimental tones | ✅ |

| Strong form, perfect balance and symmetry | ✅ |

| Motifs inspired by ancient bronzes / dynasties | ✅ |

| Museum-grade sculptural details (carving, lines) | ✅ |

| Bronze-style feet, handles, or rimmed lids | ✅ |

| Known early style (pre-1995) craftsmanship | ✅ |

This checklist is a valuable tool for collectors, curators, and scholars alike. In a world where fakes abound, especially of older Qing and Ming porcelains, Yi Yun’s Zisha pots stand out — not just for authenticity, but artistic soul.

The Authentication Process So Far

Now that I’ve shared how I came across this beautiful teapot and what I’ve learned about the artist Yi Yun (Lu Shuoliang), I’d like to walk you through the steps I’ve taken to try to authenticate this intriguing piece.

1. Museum Comparisons:

My first course of action was to scour the web for other examples of Yi Yun’s work. I found several pieces held in museum collections around the world, including in China and internationally. The similarities in texture, form, poem usage, and applied motifs were incredibly striking. I’ve included some comparison photos below so you can judge for yourself.

Below are some museum examples of his work.

2. Expert Consultation — Peter Combs:

I then reached out to Peter Combs, a widely respected and world-renowned Asian art expert known for his appraisals and auction work. I sent images and a description of the teapot to him for review. While I haven’t received a reply yet — it’s been four days and the suspense is killing me — I’m holding out hope that he’ll respond soon.

3. Attempt to Contact the Artist:

Digging deeper into Yi Yun’s background, I discovered he is not only alive but also the founder of an arts institute and has his own studio website. Unfortunately, the site only lists a QQ number, a WeChat QR code, and a phone number. Due to UK and China communication restrictions, I wasn’t able to use QQ or register WeChat, despite several hours of trying. I haven’t tried calling yet, as I don’t speak Chinese.

4. Reaching Out Through Community Groups:

I then turned to the Yixing Teapot Facebook group, asking if anyone based in China could kindly pass a message on to Yi Yun or his studio. So far, no luck, but I remain hopeful. I’ve included the post in the article below.

5. Group Feedback — Mixed Responses:

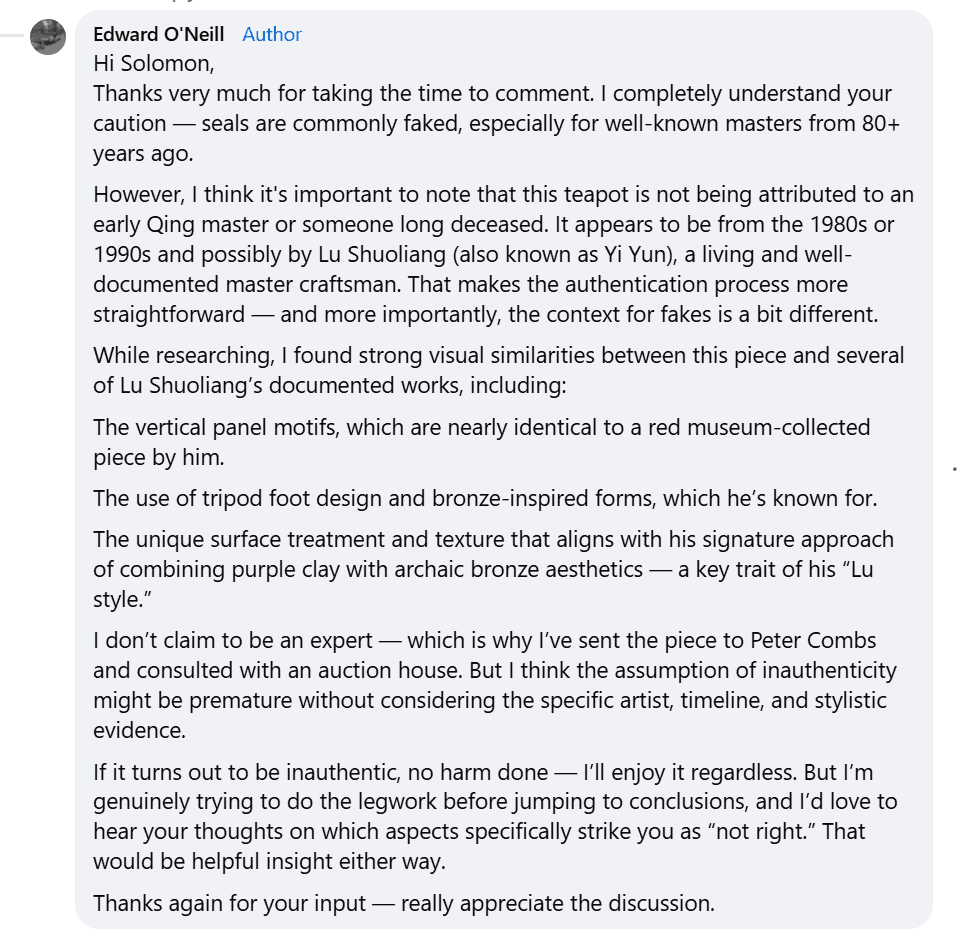

Naturally, not everyone agreed with my excitement. One commenter dismissed the piece outright, claiming it doesn’t look authentic and that seals are easily faked. I appreciated the honesty, but I also felt their response may have been based on quick judgment. I replied with a calm, respectful explanation pointing out that this isn’t a Qing-era piece — it’s a potential 1980s or 1990s teapot by a living artist — and that the criteria for authenticity are different.

I received no reply to my response on the above question, so none the wiser why this expert felt the pot was wrong.

Another commenter felt the craftsmanship didn’t meet the standard of a master, but admitted they hadn’t seen the teapot in person. Again, I responded that if the pot is early in Yi Yun’s career, it may differ from his later, more refined works — but because he is alive, we don’t have to guess. If we can get in touch, we can know definitively.

6. My Logical Reasoning — Why It May Be Real:

The last thing I want to share is my thought process, which I discussed with a fellow dealer. Here’s the logic:

Fakers typically target long-deceased masters, not living ones who can immediately confirm or deny a piece’s authenticity. Faking a living artist is a risk. And if this was a high-end fake, why did it end up at a car boot sale in South Wales for £3? The quality is too high for mass production, and if someone were going to fake Yi Yun’s name, surely they’d try to push it through an overseas auction house for thousands.

So that’s where I am: in limbo. I believe I have something genuinely special, but without confirmation from the artist or Peter Combs, the mystery continues. One way or another, I’ll keep chasing the truth — and I’ll update this article as soon as I hear anything new.

Final Thoughts: The Joy of the Journey

Whether this teapot turns out to be an early masterpiece by Yi Yun or simply the work of an exceptionally talented but unknown craftsman, the experience has been priceless. It’s a reminder that treasure hunting isn’t always about the money — it’s about curiosity, learning, and the thrill of discovery.

I’ve gained far more than I ever expected from a £3 purchase at a muddy car boot sale. I’ve explored museum archives, studied the work of a living master, learned about clay, glaze, Chinese inscriptions, and Zisha forms. I’ve had conversations with experts, skeptics, and fellow collectors. It’s been frustrating at times, but equally thrilling — and it’s exactly why I keep searching through those boxes of “junk” at 7 a.m. on a damp Thursday morning.

If I get confirmation from Yi Yun’s studio or Peter Combs, I’ll share it here. If new evidence comes to light that changes everything, I’ll include that too. This is an ongoing investigation, and I want this article to be a living record of that journey.

Until then, thank you for reading, for indulging my passion, and maybe even for getting just a little excited with me. Because who knows — maybe your next great discovery is waiting in a £3 box at the edge of a field too.

When I know, you’ll know.

Table of Contents